Close your eyes for a few moments, and take a walk in your mind. Wandering urban backstreets and city corners, you pause at a piece of graffiti where a woman with bright pink hair is speaking into the night beneath a spray-painted cosmos of planets and stars. A group of curious-looking people in warm coats stand around her, listening intently. To the average passer-by, we are an intriguing collection of oddballs standing around, loitering on an almost freezing November night. They would be right.

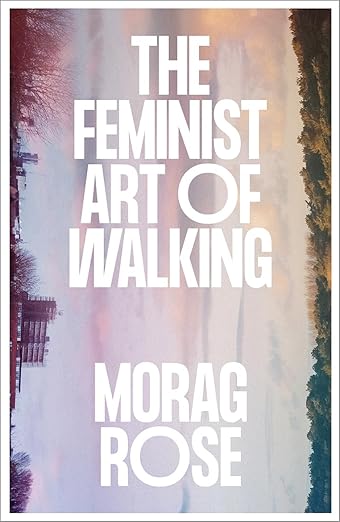

We gathered on that chilly evening for a book launch with a difference. Morag Rose, author of The Feminist Art of Walking, led us on a walk around the streets of Digbeth before her launch event at Voce Books. We stayed close to the bookshop for the duration, doing more loitering than walking whilst Morag gave several readings from the book. As founder of the Loiterer’s Resistance Movement (LRM), Morag is accustomed to reclaiming the art of loitering with intent. A Manchester-based not-for-profit collective of artists, activists and urban wanderers, the activities of the LRM form a radical context for much of this unique publication.

“I am a loiterer because I am curious, I want to explore and ask awkward questions.” – Morag Rose

Rose claims the mantle of anarcho-flaneuse, alongside performance artist and part-time lecturer in Geography at The University of Liverpool. Her new book is based partly on a PhD thesis about women walking the city, as well as LRM activities and her lived experience. She actively campaigns for better-designed public spaces to make walking and belonging easier for those living with disabilities and from marginalised groups. Rose points out that the “assumption that walking is simple: one foot in front of the other, easy does it, primal, instinctive. This assumption is a fallacy that all bodies are alike and walking comes ‘naturally’ to all”.

As for many creatives, the pandemic offered opportunities to say new things about walking and how we get around (or don’t). The Walking Publics/Walking Art: Walking Wellbeing and Community During Covid-19 initiative was an AHRC-funded project by Rose and her collaborators, which explored the potential of the arts to sustain, encourage and more equitably support walking during and following the pandemic. Our lockdown months were when I reoriented my own work towards walking art, having received an Arts Council development grant, which led to a PhD in landscape and inclusion. As a researcher in this field, I can confidently say that walking art is no longer the terrain of lone, white male artists, but an inclusive field nurtured by collectives such as Walkspace. As Rose writes, walking provides “an opportunity for multi-sensual exploration and a deep connection with space, place and communities”. Through the medium of creativity, these opportunities are extended far and wide.

Tracing our footsteps back to the book, Rose builds particularly on feminist perspectives to explore the act of walking in an inclusive and intersectional way. Integrating queer and disabled perspectives, the book also outlines issues around privilege. The Feminist Art of Walking makes assertive strides into questions of where we walk and who public space is for. Taking the reader on a journey through several locations, Rose examines mostly urban locations, with references to the rural. Beginning in Manchester, the book meanders through Liverpool, Sheffield, Eastbourne and smaller communities. The Eastbourne chapter pinpoints the start of Rose’s journey in thinking about how women walk, and the fear-based narratives that inform so much of women’s wayfinding. Rose writes of learning her ‘gender limits’ in younger life, through all-too-common experiences of harassment and intimidation. She asserts that women’s need to protect themselves is “embedded in our daily routine”, a narrative that the LRM attempts to undo. As Rose writes: “I am a loiterer because there are places I feel scared to go alone”. Most chapters in The Feminist Art of Walking are set in England, except for a spin through Ebbw Vale and Rose’s Welsh ancestry. As a resident of Cymru, I particularly enjoyed this chapter and the author’s comments on connections to place and ancestry.

“There wasn’t an actual photograph in my pocket in Ebbw Vale as I feared a relic would get crumpled or put though the wash. I don’t think I need it – the dialogue is in my head. If I do fancy a visual nudge, there’s a galaxy of images on my phone. We all walk with ghosts, ancestors and descendants wherever we go, it’s whether we choose to let our imaginations tune into them that determines the conversations we have (…) Wherever I walk now, my mother and nan are here, in my genes, my dreams, my wayfinding and my wonky footprints”.

After the official launch at Voce books (co-organised by Walkspace) our group of temporary loiterers disbanded, all the wiser and a little bit more at home in the world. This is a book about belonging on a deep level, and sharing experiences of what it means to be here. Rose reminds the reader that “you belong here and if that is not obvious then create your own welcoming committee”. Using the metaphor of desire lines, Rose asserts that a path made through intuition may well be walked by others, deepening the grooves and creating bolder paths.

The Feminist Art of Walking does just that, encouraging people of all genders and expressions to move in resistance and solidarity. What strikes me most about this book is the potentiality within its pages, and the power inherent within a simple, everyday walk. As Rose writes, walking is a source of belonging and community, solace and standing up for what we believe in; all within a passing hour, or as Rose puts it “everything and nothing written with our feet”.

The Feminist Art of Walking is available at Voce Books (online, or if you’re in Birmingham) for £16.99, from bookshop.org or your usual bookseller.